#Nutraceuticals #Evidence-BasedHerbals #Evidence-BasedMedicine #SafetyOfHerbals #MedicineTrees #MedicinalHerbs #MedicinalPlants #HerbalMedicine #PlantMedicine #TakingLeadFromNature #Herbals #MedicinalPlantsAsFood #FromFoodToMedicine #Superfoods #ClassificationOfHerbalMedicines #TCM #SnakeOil #DrugRegulation #FDA #EMA #MedicineOfSuchRareExcellence #Panacea #OTC #Aromatherapy #Charlatan #Nutraceuticals #SpicesAsMedicine #Aromatherapy

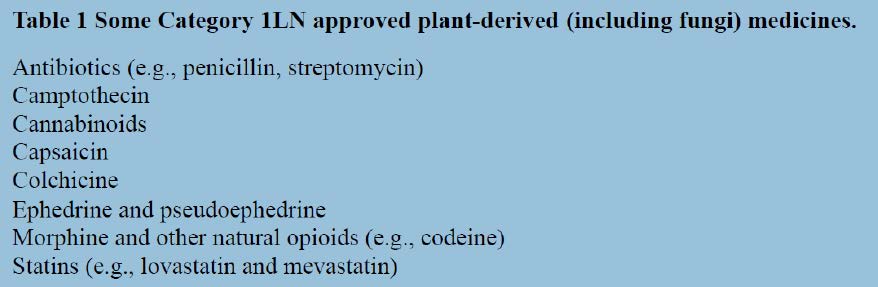

The medicines we post on may be obtained directly from plants or indirectly through modifications of natural plant molecules. By plants, we include fungi and microbes that produce substances of medicinal value (e.g., antibiotics, immunosuppressants and statins).

Plant medicines have different levels of evidence to support their clinical use. Some have been used since pre-history, inferred only from human artifacts or from plant molecules recovered from the mortal remains of our prehistoric ancestors. Some plants have a documented history of medicinal use stretching over millennia. Others have emerged through the rigours of formal laboratory investigations and challenging clinical trials demanded by modern drug regulatory authorities set up in the aftermath of the thalidomide disaster that caused an estimated 4000 perinatal deaths and 6000 severely deformed newborns. Others still are based on simple hearsay or on the authority of a latter-day snake oil pedlar.

In the rules, we state that we welcome posts on the whole range but ask that poorly validated medicines are not portrayed as established therapy.

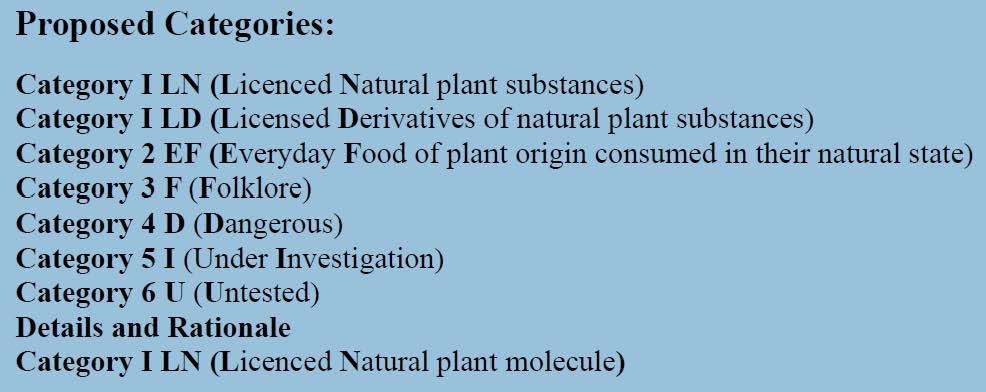

In this post, I wish to comment on the levels of evidence claimed to support the use of plant medicines, and to suggest their categorisation, working backwards from those that are most rigorously validated to those that are close to snake oils and Molière’s 17th century Oviétan, ‘a medicine of such rare excellence that it cures more maladies than one can enumerate in a whole year’ or as an early editor of the British Medical Journal put it, ‘a cure of almost all diseases to which flesh is heir’.

Details and Rationale

Category I LN (Licenced Naturalplantmolecule)

In this category we have medicines such as the analgesic morphine (from the poppy), the cholesterol-lowering statins (from mushrooms), the anticancer drugs paclitaxel (from the yew tree) and vincristine (from the periwinkle), and the antimalarial drug artemisinin (from Artemisia annua). Formulations (tablet, injections etc) of these drugs are licensed by leading drug regulatory authorities and their efficacy and safety profiles are well known. For historical reasons many of the plant medicines already on the market in this group have followed a less demanding pathway to registration than would a new candidate plant molecule. Even the most demanding observers would agree that plant medicines in this category have a place in therapy when used as recommended in the officially approved drug data sheets.

A product licence does not necessarily mean that we know all about the drug concerned. Many drugs have been withdrawn from the market years after their first licensing as wider use experience identifies adverse outcomes not captured in the necessarily small and short-term trials used to support their licence applications. Some such drugs have severe adverse profiles particularly when used outside of their approved indications. Dramatic and tragic examples are the epidemic of drug addiction to licensed opioid analgesics, the abuse of hypnotics and anxiolytic medicines, and the potentially deadly heart abnormalities which some anticancer drugs cause. Some modern medicines deemed to be safe enough for over-the-counter use have subsequently been withdrawn (e.g., some antihistamines withdrawn because they cause potentially fatal irregular heartbeats in some individuals).

Category I LD (Licensed Derivativeof natural plant molecule)

This category includes synthetic medicines derived from lead molecules obtained from plants, usually because they are thought to be safer, more selective, or more effective but often to obtain patent exclusivity. The medicines in this category have also gone through the rigours of drug regulatory licensing by well-respected authorities. These new medicines may or may not deliver on their therapeutic promises, but often lead to discoveries of new clinical applications. Estimates suggests that perhaps one in five currently prescribed medicines have emerged from plant-derived lead molecules. For example, many statins are chemical modifications of those that are naturally present in some mushrooms, and modifications of the caffeine molecule in tea have led to major therapeutic innovations.

Category 2 EF (Everyday Food of plant origin consumed in their natural state)

Here we have plant products that serve as food but are often over-promoted as superfoods. These include various berries, citrus fruits, pomegranate, papaya, various leafy vegetables, and grains, sold as the natural product, or as extracts often co-formulated with other nutrients. The claims often include terms such as ‘rich in antioxidants, flavonoids, various vitamins or fibre’ or ‘improves immunity or cardiovascular health’. In the presence of deficiency, these foods can of course be lifesaving, but claims that they deliver something extra-ordinary are generally far-fetched and hatched in the marketing departments of companies or in the minds of zealots. Formulated into palatable dosage forms they are often sold as nutraceuticals for those aspiring to be super fit or wanting to live longer. There is a need for them but not in their oversold forms.

Category 3 F (Folklore)

This is a category of plant medicines with a long history of generally safe use, but with very little objective evidence that they are effective for any well-defined clinical condition. A placebo effect is the best explanation for their beneficial effect. Included here are plant products that are sold widely in reputable health-food stores or as Over-The-Counter (OTC) remedies in pharmacies. Regulatory bodies such as the US Food and Drug Administration may classify them as Generally Recognised As Safe (GRAS) medicines and the European Medicines Agency as monographed medicines screened by experts.

Example of plant medicines in this group are various teas such as chamomile, ginseng, valerian, chrysanthemum, and mint. If they work, why not? They are generally safe. For self-resolving symptomatic relief, they are often as useful (or useless) as any licensed OTC non-herbal medications.

The vast majority of the thousands of spices used regularly to spice our foods, and to turn mortals into chefs and chefs into master-chefs fall into this category when promoted as medicines. Some have more supporters than others (e.g., turmeric and ginger). There is little controversy about their use as taste and flavour enhancers, but the evidence needed to transition them into Category I medicines is just not there.

Fragrant volatile oils or their extracts are also in this category. Some are often added to licensed or pharmacopoeial formulations (e.g., peppermint, camphor, and menthol) but on their own they are not Category I medicines. As massage oils, they are what we have previously referred to as medicines for the soul. This is the concept enrobed in aromatherapy, the term coined in 1937 by one of its earliest proponents Rene-Maurice Gattefossé, but a practice that dates back centuries and arguably millennia when our ancestors burnt aromatic herbs and woods, often with religious chanting) to drive out the evil spirits that caused illness.

Category 4 D (Dangerous)

Plants and plant products in this category are often initially in Category 3 but are then found through modern epidemiological methods and causality assessments to have serious, potentially lethal, adverse effects such as liver and renal toxicity, teratogenicity (causing foetal malformations) or carcinogenicity. Sale of such plants is usually banned, or their toxin content controlled and limited, by regulatory authorities, once the dangers become known, but in the world of folklore and hearsay, information filters through slowly and unreliably. Two widely studied examples are medicinal plants containing liver-toxic aristolochic acid or high pyrrolizidine alkaloid content. In this category, we also have Category 3F plant remedies surreptitiously ‘fortified’ with known active molecules. The US Food and Drug Administration, for example regularly seize herbal remedies that have undeclared substances such as sildenafil (Viagra molecule), steroids and synthetic anti-inflammatory compounds in them.

Category 5 I (Under Investigation)

These are well defined plants with significant formal investigations but not yet shown to have any specific clinical application. They are often Category 3 F (Folklore) plant remedies. This may simply reflect their market success. Ginseng, garlicm and echinacea are examples of the latter.

Category 6 U (Untested)

These are latter-day secret remedies, usually promoted as novel discoveries by unscrupulous merchants to make a quick buck. Believe and you will be cured, the promoters say but put your money in the box as you pass Go.

Alain Li Wan Po, the author, has previously served as member of the UK Committee on Safety of Medicines and Professor of Clinical Pharmaceutics at the Universities of Nottingham, Aston in Birmingham, and Queen’s in Belfast. He has also acted as consultant to leading Pharma companies, including Roche, Squibb, GSK, Ciba-Geigy, Bayer and Boots, and Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics.

Leave a comment